Here is ‘Britaly’BY LUCA BELLARDINI

- 2 November 2022

- Posted by: Competere

- Category: Senza categoria

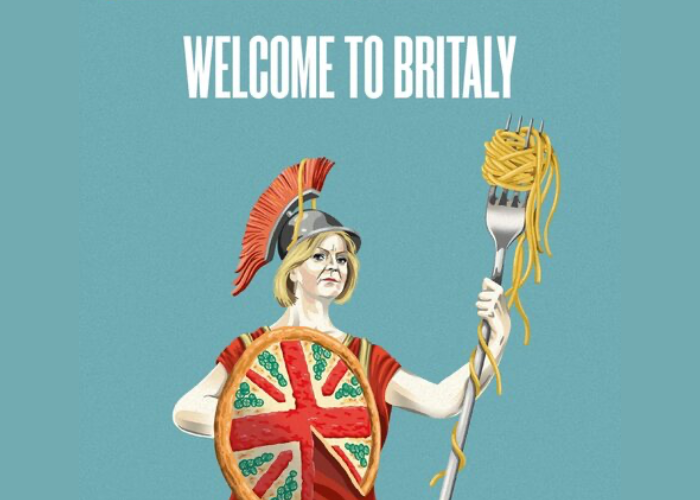

The now famous cover of the Economist spoke of ‘Britaly’, understood as an “Italianisation” of British politics. Beyond the rather cloying stereotypes, we cannot deny that, following the 2016 EU referendum, that country’s institutional system of that country has undergone one shake-up after another, ending up by giving international observers not exactly an edifying spectacle. Liz Truss’ premiership is going to set a negative record in terms of duration. Anyway, is the moment in British history really so grave after all?

SO, WHAT ABOUT GLOBAL BRITAIN?

If ‘Britaly’ is a concept worth discussing, we should look at Italy as well. First of all, let’s leave aside the turmoil’s “systematic” component: in fact, the inflationary shock caused by the central banks’ easing of money supply, exacerbated by the further surge in energy prices — resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine — is common to the entire West. Rising interest rates are a necessary medicine, yet a reversal in price dynamics still seems out of reach. The geopolitical tensions are well known. Equally evident is the marked loss of value that both the pound sterling and the euro have suffered over the most recent months.

The United Kingdom would like to think of ‘Global Britain’, because of its long-standing cosmopolitan vocation (we talked about it here); but the sudden change of both the sovereign and the head of government, with a small financial storm in the middle, clearly calls for pausing and reflecting. Maybe London should think of itself before the world?

ITALY’S PROSPECTS

The answer can be sought in the Peninsula, where the Meloni cabinet presents itself with a programmatic framework and an ideal inspiration not far from those of the Tories who have been in Downing Street since 2010. In the recent past, there was still mistrust towards communitarian institutions, a severe criticism of an institutional set-up in which the differences between Member States were crushed rather than fruitfully exploited, and the denunciation of a Europe that is focused on hyper-regulating narrow things but little devoted to the grand strategic issues.

Italy’s current largest party has never remotely proposed leaving the EU, yet its vision is not too far removed from Brexiteers’. At present-day, also, its Eurosceptic theses do coexist — without any contradiction — with fully acknowledging how important it is to have a country that be well integrated within the EU, perhaps the protagonist of a new course. More in detail, its platform reminds of the so-called ‘One Nation conservatism’, distinct (at least in practice) from the Thatcherite vision (which is taken up, however, in respect of European affairs). In foreign policy, then, both Meloni and Johnson or Truss have always argued for a tough opposition to autocracies’ expansionism, with a staunch defence of the aggrieved.

PATRIOTISM CAN (MUST!) BE OPEN

In this sense, neither of the two countries should set itself the problem of ‘thinking at home first’; it should never close itself off from the world. Italy’s and the UK’s problems are conspicuous, but the solution should not be sought in isolationism. Moreover, Rome’s forthcoming budgetary law is likely to rely heavily not only on PNRR funds but, also, on the room for manoeuvre offered by the EU cohesion policy (particularly in the energy field). For its part, London no longer receives European flows (which, albeit less substantial than in Italy, were not negligible at all); however, it can still count on a centrality in the world financial system that is an imperishable asset, capable of withstanding even the most turbulent periods.

In Rome’s new government, the prominence given to ‘Made in Italy’ — endowed with the competencies once associated with foreign trade — gives us a positive feedback, as does the idea of a ministry specifically addressing the problems of the South and how to unleash the country’s maritime potential.

In short, Britaly’s political developments send a clear message: let us be open and competitive, in a safer world, without bureaucratic fetters from outside. Even in the age of ‘deglobalisation’, rulers’ cleverness may prevent national demands from erecting insurmountable barriers. After all, to utter the famous patriotic — let us say chauvinistic — monologue in Shakespeare’s ‘Richard II’ (‘… this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England!’) is John of Gaunt (now Ghent), born in Flanders when the English royals — a British king and his French queen consort — were on a business trip to the beating heart of Europe. A few miles from Brussels.